Rodney Bollie’s mother taught him to consider education a privilege. Today, his non-profit helps young people in Liberia get the hands-on training they need for futures in STEM careers.

After Escaping Civil War, A MITRE Engineer Pays It Forward

MITRE’s Rodney Bollie spends his workdays researching and designing secure and resilient 5G communications networks from our headquarters in McLean, Virginia.

But Bollie’s work today is a far cry from the classrooms in his birth country of Liberia, where he studied electronics engineering in a poorly equipped laboratory with no access to computers. Family friends arranged for his move to Maryland to continue schooling, which led him to an engineering career at MITRE, where he develops technology to make the world safer.

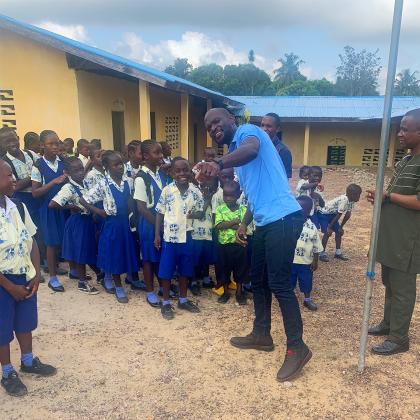

Today, Bollie (pronounced “bowl-ie”) and his wife, Dr. Sylvia Bollie, lead the Institute of Basic Technology (IBT), a nonprofit organization that they founded to provide science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education and career preparation to high schools serving Liberia’s poorest communities. At the 2023 Becoming Everything You Are (BEYA) STEM Awards, Bollie accepted a Science Spectrum Trailblazer award in recognition of the thousands of Liberian students he has helped learn about technology and prepare for the job market.

“At MITRE, we look to our next generations as the successors in our quest to solve problems for a safer world,” wrote Jason Providakes, MITRE president and CEO, in his letter nominating Bollie for the award.

“Thanks to Rodney Bollie—a stunning representative of MITRE’s commitment to corporate social responsibility—the spread of STEM education has widened and will help prepare today’s students for tomorrow’s work.”

A Youth Scarred by Trauma

Bollie’s eventual asylum in the United States, his education, and, in 2019, his joining MITRE as a communications networks engineer, follow a harrowing story that’s the stuff of movies.

He was 12 when the war began, a student at one of the best parochial schools in the country. His mother had graduated from secretarial school and found a position as a secretary in the U.S. Information Service. When the United States evacuated all but non-essential workers from the country, her manager, foreign service officer David Krecke, recommended that they move into his house on the U.S. government-operated Greystone housing complex.

Between several attempts to flee Liberia, Bollie and his family stayed at Greystone, protected by a peacekeeping force, until a ceasefire was brokered. By then, he and his four brothers lived under constant threat. The militia were just as likely to kill them as conscript them and send them to war.

The family escaped to the Ivory Coast in 1992 and lived as refugees until 1995, when they returned to Liberia. In 2001, Krecke, by then stationed again in the United States, arranged for Bollie and his sister to join them in Bethesda, Maryland.

Education Opened Doors to Work, Health, and Appreciation

An associate degree in computer engineering from Montgomery College led to a bachelor’s in computer and electrical engineering from the George Washington University and a master’s in information technology from the University of Maryland University College. Now he’s a Ph.D. student in Information Systems and Communications at Robert Morris University.

Rodney worked hard to assimilate into the American culture. All the while, he worked at the campus bookstore to keep money in his pocket. He remembers his first real interaction with a computer taking place at Montgomery College. And he dreaded chemistry class because he had never learned to mix chemicals and had to learn. He struggled to write papers. Fireworks on the Fourth of July traumatized him.

A news interview with a soldier, home after fighting in Iraq, helped him understand that he was experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder. Finally able to articulate what haunted him, Bollie worked to overcome it.

He never forgot his mother’s insistence that education was a privilege, and the realization that people with no obligation to help him had taken him in. “I made it my duty that if I were to succeed in any way and get a job, I wanted to be able to do something similar for someone else,” Bollie says.

“When I met my wife, I told her I would really like to help out in Liberia,” he says. “Together we agreed that we would start off with high school, because that was where the need was the greatest.”

Technology Opens Pathways to the Future

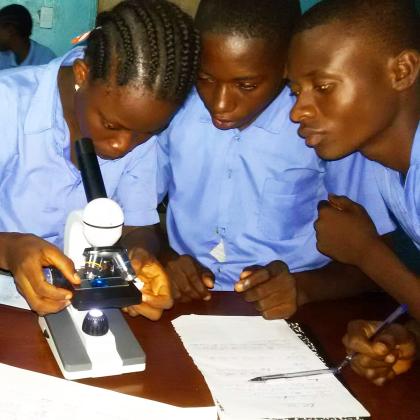

The IBT provides high school students with access to microscopes and computers—and of course chemistry—supplementing the education their schools may not be equipped to deliver.

IBT students learn computer programming in Python, basic computer networking, and system troubleshooting. This year the institute introduced the students to drones and is teaching them to write code that directs the drone operation.

Bollie says they realize many of these students won’t have the same opportunities he and his sister had to leave the country. (Bollie’s sister now lives in Atlanta, Georgia.)

“At the very least, they can stay in Liberia and do something for themselves, whether opening their own shop as a computer repair technician, building computer networks, or building websites,” he says.

He also records a podcast, where he has shared his own story, and invited other successful Liberians from the United States or other parts of the world to tell theirs. “It’s a way to help the students back home—a source of inspiration that they can make it, too.”

To learn more about the program and listen to Bollie’s podcast, visit Institute of Basic Technology.

Join our community of innovators, learners, knowledge-sharers, and risk takers. View our Job Openings.